In My Dreams You Survived

CW // Death

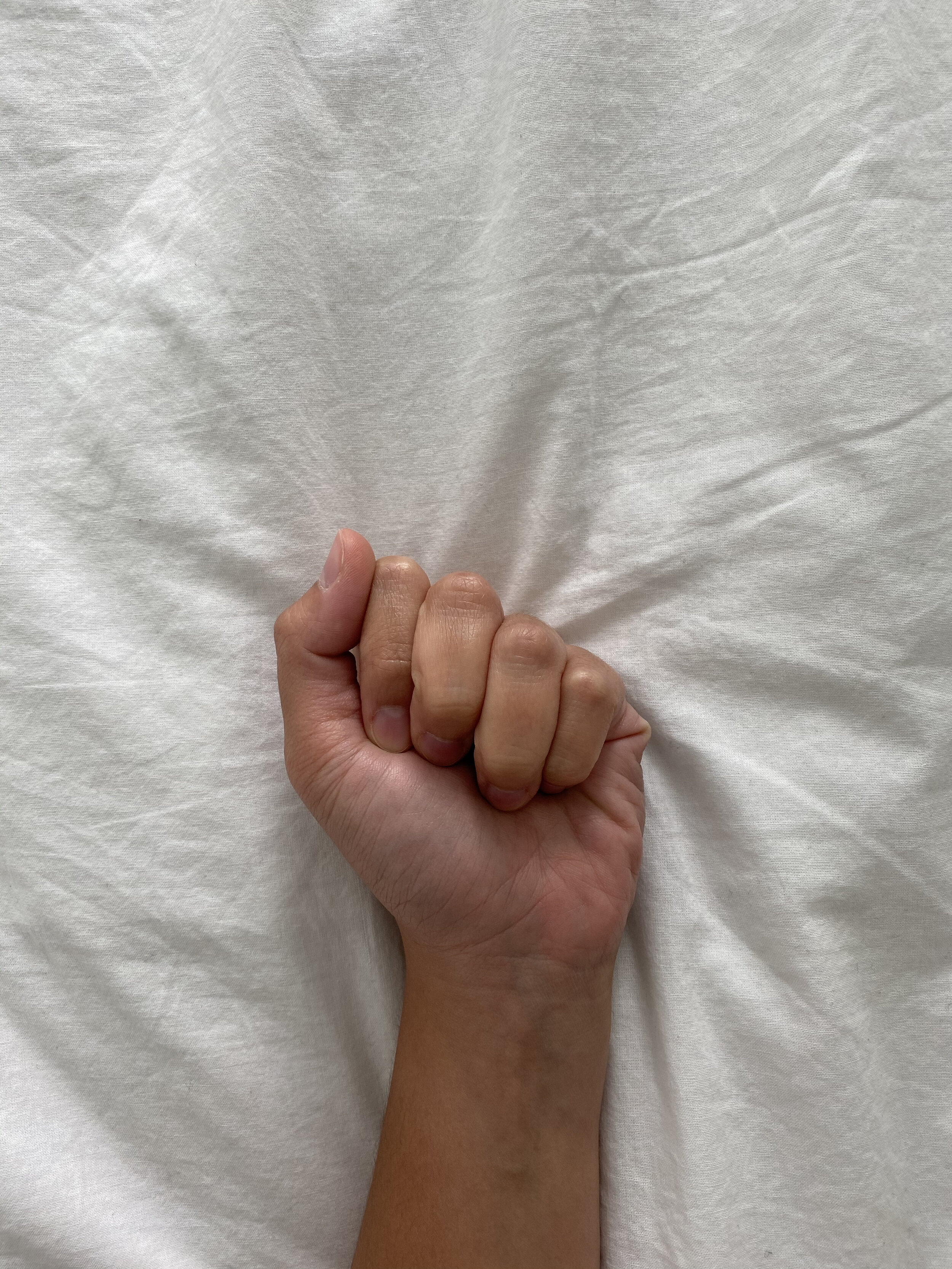

The term “tangible” originates from the Latin verb tangere—to touch. Grief is intangible. I can’t hold it in my hands, but it’s simultaneously a bodily experience. The end of a loved one’s physical existence causes grief. The grief I carry, its weight, is something I can feel in my body.

There are layers to the intangibility. Not only is loss itself intangible, but the reality I find myself thrust into feels impossible to grasp as well. Grief grows more abstract with time. I remember on the first day, thinking that it was the most difficult day of my life. I didn’t think it could get harder, and everyone told me grief would get easier to navigate with time. But it doesn’t get easier. It just gets more abstract. With every passing day, the gulf between then, the time she was still here, and now, the time I am alive without her, widens. Some days these truths feel foreign and I’m not sure how to exist in them. There’s an exhausting dissonance there; I am constantly trying to internalize something that my entire being rejects.

I have so many questions that I know will never be answered. Some days these questions are untethered and weightless. When they swarm my head all at once, they dominate the soundscape of my mind like cicadas in the summer. Their buzzing is only overpowering because of its infinite multitude, its omnipresence.

The intangibility of grief relates to how privatized it is, at least for me. Because the pace of life isn’t conducive to addressing the gravity of loss every day, my grief is relegated to the private sphere. It is rarely discussed in public, and there is a lot of distance between my public and private personas, although there is never any emotional distance from the death itself. I have accepted that the distance between the everyday and the overbearing trauma helps me survive.

When you can touch something, it can be defined—it has a beginning and an end. When I hold an apple in my hand, the apple exists in that space and is limited to it. Grief is elusive. It evades definition and understanding. It’s borderless; it has no clear beginning or end. Sometimes the grief feels arbitrary, too, when seemingly unrelated situations and thoughts can be triggering. When grief is undefined, every single thing that happened before or after her death can somehow be related to it in my head. The grief is everywhere, it permeates every aspect of my life in expected and unexpected ways. Many things feel out of reach—her, the life she would have lived, the lives she would have touched, the good she would have put out in the world. All the future she will not have.

The undefined nature of grief is affirmed by its ever-changing dynamism. It feels like a cruel game with no winners; I struggle to keep up with its arbitrary and inconsistent rules. I am making my way up a never-ending, shifting, spiraling staircase. Some days the staircase is wide enough for people to join me, hold my hand, and rest with me when needed. Other days, it’s dark and narrow, and I stumble to find my way up alone. The staircase is unsteady and never-ending; it transforms ceaselessly and disorientingly, taking on new and sometimes unexpected configurations.

Searching for a sense of closure often feels futile, because I don’t believe there is an “end” state or a definite moment of closure to things like this. The way that we grieve is inextricably linked to who we are, and who we are is constantly evolving and adapting. The grief will take many forms as I change, encounter new people, and have more experiences.

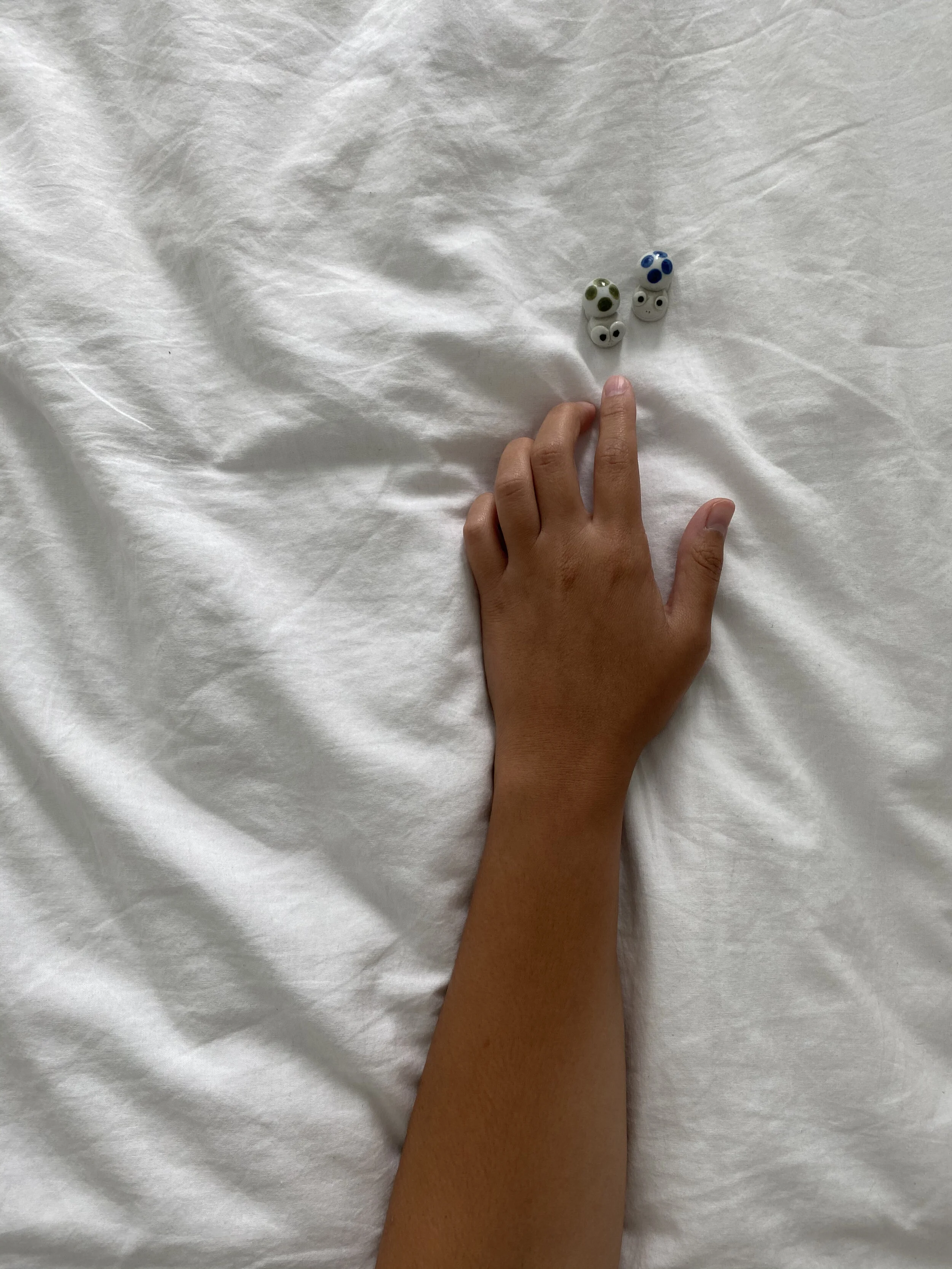

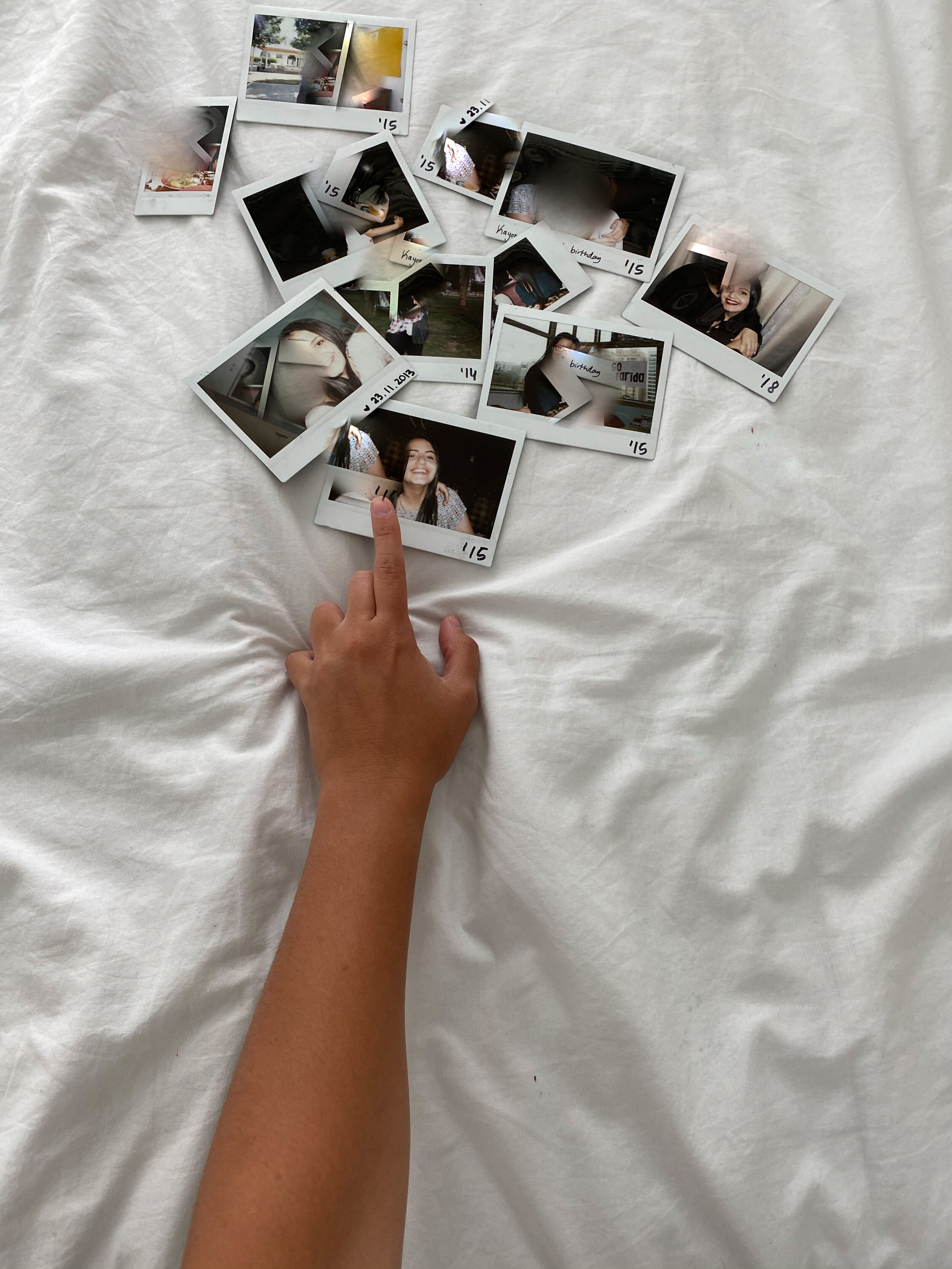

A few months ago, I thought I lost one of the ceramic turtles she gifted me. There’s two of them—she said they were the two of us—and the idea of literally having lost one of them was incredibly overwhelming. The loss was luckily averted as I soon found the turtle, but ever since then I’ve been thinking of the physical evidence we have of a relationship—and the physical evidence we have of being alive. We attach so much meaning to these inanimate objects that remind us of someone who was once animate. We keep these objects in our homes, sometimes on display or out of reach, so as to be protected. I keep these mementos in casual spaces I use daily. I acquaint myself with the objects that remind me of her, and I see some of the photos every day. By doing so, I welcome her memory in the space I inhabit.

I’ve heard many analogies for grief, all of them involving physical experiences. There’s the analogy of waves, with an ebb and flow, or a rhythm. Some relate grief to an open wound, one that at the beginning, is exposed to the outside world and is thus consistently painful, but eventually scabs and lasts as a permanent scar. Or they say that grief is an immense amount of love with nowhere to go. My grief is love, but it also anger, fear, anxiety, helplessness, confusion, numbness, dissonance, loneliness, regret, resentment, sadness, frustration, and unrelenting, incommunicable pain. I’m yet to hear an analogy for grief that accurately conveys the incorporeal nature of it. My grief is a shapeshifter. It transforms itself, and takes on a life of its own.

We like to think our memories are reliable and consistent, but our memories can and do change overtime. These changes are a product of how, when, and why we access our memories. The more we replay a memory in our heads, the more susceptible it is to change, so perhaps our memories of the dead are more altered than others. When memory is the one of the few places she still exists, and my memories of her are distorted or somehow changed, that is another loss.

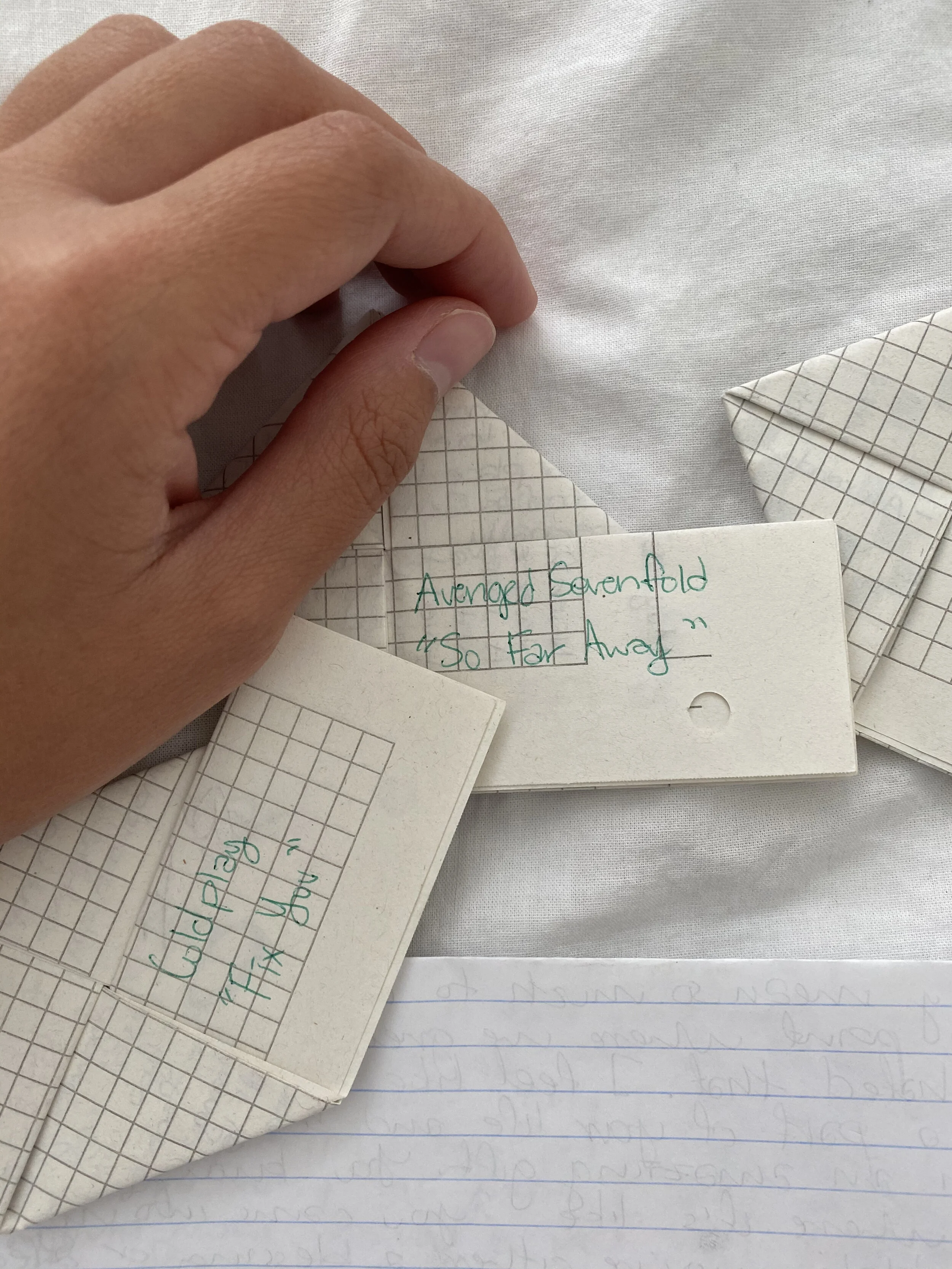

Some days it’s difficult to remember things about her and our friendship that aren’t prompted by a photo, and that’s why I appreciate when memories are tangible. Otherwise, it’s hard to distinguish what actually happened and what is imagined. The boundaries between memory, reality, and imagination are often blurred. Are our dreams of the dead new memories with them?

Documentation has been a major component of my mourning process, as I mourn her and the person I was before the loss. Documentation can offer some solace from the transience of everything. Some days, I am overwhelmed by the feeling that everything is fleeting - that there is nothing tangible or real to hold on to, that life-altering events can happen so quickly and unexpectedly, that someone who was real and so full of life can be taken so suddenly. After she died, I experienced major changes in my sense of self and identity. Documentation became increasingly important, as I became cognizant of my identity forming, shifting, and changing in intriguing and unique ways throughout the mourning process. Documentation reminds me that I am here, I am real, and that she was also here, and is still real.

As with many things, catharsis only comes with dismantling trauma. So here I am. Trying to sit with it, hold it, crack it right open… Losing her felt like life had lost all its taste, its color, its beauty, and I spent months learning how to love life again. Some days it feels so real that I can’t breathe, and other days her death feels like a dream, like it never actually happened. I miss her every day, and that will never change.

Grief makes an island out of its bearers. It convinces us we are alone in our pain, and attempts to dissuade us from developing connections to those around us. I resist the temptation to retreat to a silent place all by myself. It is undoubtedly easier to isolate, but I hope my honesty and openness about the mourning process helps others manage their grief, or at the least feel less isolated within it. I know that I have been graced, over and over again, by community love and support. If we allow ourselves, we can find our way home through the hearts of other people. We found home in each other, even if momentarily, and now our roots bind us together in perpetuity. ◆